The latest in chronic HBV & HCV treatment

Careful documentation is essential in determining the optimal course of therapy for an individual patient.

Article by

Roger Williams, CBE

The Institute of Hepatology, London, The Foundation for Liver Research

Περιοδικό Ιατρικά Ανάλεκτα/ Τόμος Γ’ – Τεύχος 9, Αφιέρωμα στην Επείγουσα Ιατρική, Μέρος Α’ Παθολογία

Chronic HCV infection

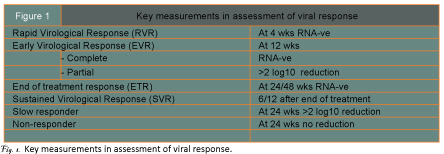

The first key event (figure 1) is whether a rapid virological response (RVR) is obtained with a negative HCV RNA at 4 weeks. Seen in around 20% only of genotype I infections, frequencies are considerably higher with genotype II and III. A RVR predicts an 80% – 90% chance of obtaining a sustained virological response (SVR) which is the ultimate goal of treatment. The next key measurement is at 12 weeks – early virological response (EVR). A complete EVR with RNA negativity is also highly predictive of an SVR whereas with a partial EVR will achieve this. No response makes later clearance of the virus very unlikely and in clinical practice is usually taken as an indication for discontinuing therapy. Slow and non-responders with either some or no reduction in viral load at 24 weeks are also important to define as even a partial response to antiviral therapy may lead to improvement in histological appearances and to reduced frequency in later life of HCC1.

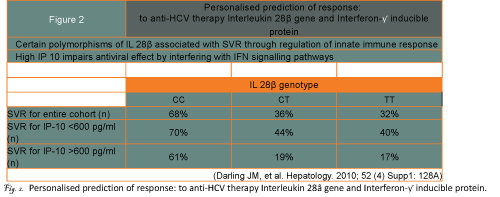

Being able to confidently predict the chances of obtaining an SVR before starting on treatment would represent a major advance. Distinct gene signatures in liver tissue and blood have been reported and there are many papers currently on IL-28B gene polymorphisms involved in regulation of the host?s innate immune responses. The chances of an SVR are much higher for the CC genotype than for CT and TT genotypes (figure 2)2. Response rates are even less with the combination of an unfavourable IL-28B and a high serum level of interferon gamma inducible protein which interferes with Interferon signalling pathways in the liver. How such pre-treatment prediction will fare with the higher responses obtainable with the new protease and polymerase inhibitor drugs is not yet known.

Whether IFN alpha -2a or 2b is used in the current standard of care treatment regime marks little difference. What is important is an adequate dosage of Ribavirin as this agent has a major influence in preventing relapse after cessation of treatment. Overall SVR?s in genotype I naive patients are around 50% – 55%, but when there is a RVR as well as a low level of viraemia (<600,000 IU/ml) pre-treatment, SVR?s as high as 80% can be obtained and the period of treatment shortened from 48 to 24 weeks. Similarly for genotypes II and III – when overall SVR?s are higher at 70% – 90%, when an RVR is obtained, treatment can be shortened from 24 weeks to 12 weeks. If risk factors for impaired responsiveness, namely, obesity and severe fibrosis/cirrhosis are present, the duration of the first course of treatment should be extended from 24 to 48 weeks. For slow responders extending the duration of treatment from 48 to 72 weeks gave a substantial increase in SVR from 19% to 38% consequent on a marked reduction in relapses from 59% to 20%3.

A difficult question is whether retreatment is of value in genotype I non-responders or relapsers. Identifiable reasons for the initial failure of treatment may be correctable such as inadequate Ribavirin dosage and interruptions in therapy. Weight reduction in the obese should be attempted but is often difficult to achieve and in one trial of subjects weighing >85kg, increasing the dose of Ribavirin to 1600mg daily gave an improvement in SVR of 28% to 47%4. In the EPIC 3 retreatment trial, SVR?s were 38% for the relapsers and 14% for non-responders5. In the REPEAT trial, treatment duration was extended from 48 – 72 weeks with a doubling of SVR in non-responders – 8% to 16%6. Both the EPIC 3 and the REPEAT trials had a high percentage of cirrhotics – the hardest to treat category which emphasises the need for early diagnosis and treatment. Both trials showed that further treatment was pointless if there was no EVR at 12 weeks.

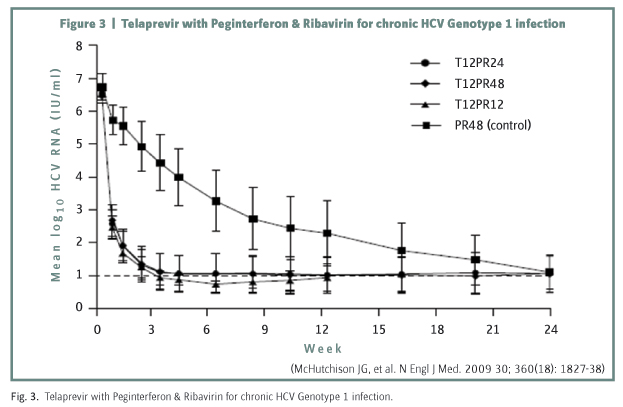

The new potent antiviral drugs, namely, Telaprevir and Boceprevir specifically inhibit protease activity of the virus. Phase 3 trials have now been completed and mid 2011 is the projected date for release onto the market. Early trials of Telaprevir as monotherapy showed that a rapid fall in viral titre over the first week was followed by a high breakthrough rate from development of viral resistance. This could be prevented by giving additional PegIFN and Ribavirin with Telaprevir being discontinued after 12 weeks and the PegIFN/Ribavirin continued for a further 12 weeks (figure 3). The phase 2b PROVE trials of this triple therapy regime in genotype I naive subjects showed over 80% achieving a RVR giving an SVR rate of 61% at 24 weeks versus 41% in the control arm of PegIFN/Ribavirin given for 48 weeks. Breakthrough and relapse rates were low7. Thus not only is a higher SVR obtainable with Telaprevir but treatment duration is shortened. In the PROVE 3 trial of non-responders and prior relapsers, SVR?s of 39% and 69% were obtained compared with 9% and 20% respectively in control arms. Viral breakthrough in the non responders was high at 22% which is not surprising as these patients were essentially on Telaprevir monotherapy. Side-effects of rash and anaemia lead to a discontinuation rate for severe adverse events of around 20%. The drug in tds dosage has to be given at exactly 8 hour intervals and as it is metabolised through the P450 enzyme system, drug interactions may occur with the commonly used statins.

Boceprevir similarly has significant side effects including anaemia requiring Epoetin support, gastrointestinal disturbances and unpleasant taste in the mouth (dysgeusia) with discontinuation of therapy in around 25% of cases. In contrast to Telaprevir, the drug is started after a lead in period of Peg IFN/Ribavirin for 4 weeks. By obtaining steady state concentrations prior to the start of Boceprevir, the emergence of resistant mutations to the drug is reduced. Depending on level of RNA reduction during the lead in period, Boceprevir is given for a further 24 or 44 weeks along with PegIFN/Ribavirin. In the Sprint-I phase 2 study, the SVR was nearly double that in the control arm – 75% vs 39%8. With a RVR – achieved in nearly two thirds of the cases, the SVR was 82% and treatment duration shortened.

There is progress too in what we are all hoping for, namely, an antiviral regime without Interferon and based on oral medication only. Gane et al, reported at the AASLD

Meeting in 2009 that combining the protease inhibitor drug Danoprevir with a polymerase inhibitor R7128 resulted in rapid viral suppression over 14 days without the emergence of resistance to either compound, and confirmatory results of this approach were published recently9. Targeting different steps of viral replication concurrently, as we have learnt from HIV infection, may prevent or delay the emergence of drug resistance.

Chronic HBV infection

Controlling viral replication, as with chronic HCV infection can lead to remarkable improvement in histological appearances and long-term survival. Much of present day management is directed to the selection of most appropriate antiviral agent based on a better appreciation of the natural history of the infection, particularly of HBeAg+ve and -ve CHB and of the inactive carrier state.

Most of the patients who undergo HBeAg seroconversation with appearance of anti-HBeAg in the serum at the end of the immune clearance phase become inactive carriers with a good long-term prognosis. Serum transaminases are only minimally elevated and HBV DNA titres are either undetectable or <2,000 IU/ml. In the past inactive carriers were referred to as healthy carriers which erroneously implies a durable absence of HBV replication and of the potential for disease development. In fact, the inactive carrier state is a potentially dynamic phase with the capacity for reversion to HBeAg +ve CHB or more frequently to HBeAg -ve CHB in which viral replication occurs in the absence of HBeAg as a result of mutations in the pre-core and/or co-promoter regions10, 11. These mutations are seen most characteristically with genotype D infections which explains the high incidence of this type of HBV disease in Greece and in other parts of the Mediterranean area. A long-term outcome study of chronic HBV in 70 Caucasian patients showed that 61 (87%) underwent spontaneous seroconversion. Twenty five year survival probability was 40% in patients persistently HBeAg +ve, 50% in HBeAg -ve CHB and 95% in inactive carriers12.

For the safe categorisation of a patient as an inactive carrier, monitoring of serum transaminase & HBV DNA tire should be carried out at 3 monthly intervals for the first year and thereafter at 6 monthly intervals. Non-invasive serum markers of disease progression particularly the FibroTest and ActiTest as well as the Fibroscan can provide some guidance, but in some cases distinction of an inactive carrier from HBeAg -ve CHB may only be possible on liver biopsy. In one study a third of patients with normal serum transaminases had significant activity on histological examination13, and in another, two of nine cases in whom DNA levels were <2,000 IU/ml were found to have active liver disease14.

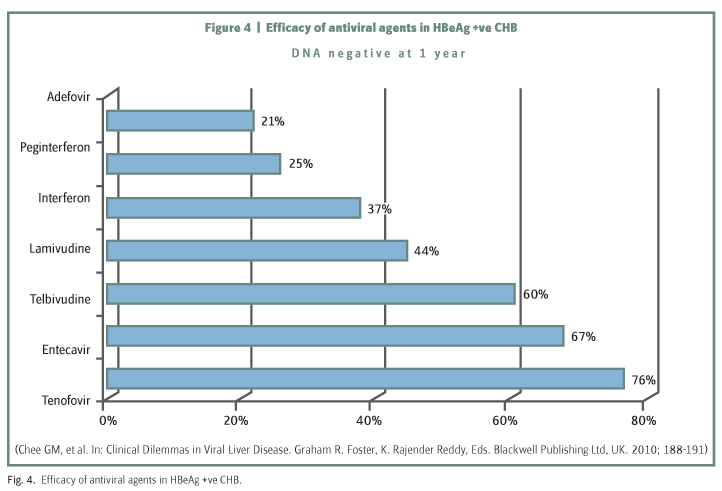

The percentage of HBeAg +ve CHB patients in whom HBV DNA levels were brought to negativity over 12 months of treatment by a number of the licensed agents now available for controlling viral replication is shown in (figure 4)15. Lamivudine though effective and relatively cheap is, unfortunately, associated with a high level of viral resistance. Adefovir also induces resistance and is not so effective in terms of HBV DNA suppression. The two most recently introduced agents, namely, Entecavir and Tenofovir are highly effective with a low induced viral resistance rate and are now the preferred agents for use in treatment of naive subjects. Both agents have a good safety profile though Tenofovir is potentially nephrotoxic and dosage has to be reduced in patients with renal impairment. Proponents of the use of Pegylated Interferon point to it as the agent which gives the highest and most sustainable seroconversion rate with a defined 12 month period of treatment. But this still leaves 70% of patients to go on to long-term treatment with oral agents. For those patients who have developed resistance to Lamivudine, the addition of Adefovir gives a satisfactory reduction in HBV DNA, although longer term the patient is better switched to Tenofovir. Entecavir should not be used as there is cross resistance with Lamivudine. Patients with resistance to Adefovir should preferentially go on to Entecavir as efficacy is reduced with Tenofovir which has a similar molecular structure to Adefovir.

Reduction and loss of HBsAg with the appearance of anti-HBs is the ultimate goal of antiviral therapy and currently there is interest in the additional value given by monitoring HBsAg level, now that a low cost automated technique for quantitative measurement is available16. HBsAg titre is correlated with that of HBV DNA and intrahepatic cccDNA levels, but only in the early phases of infection and in genotype D and not A. In HBeAg +ve CHB, low levels of HBsAg (

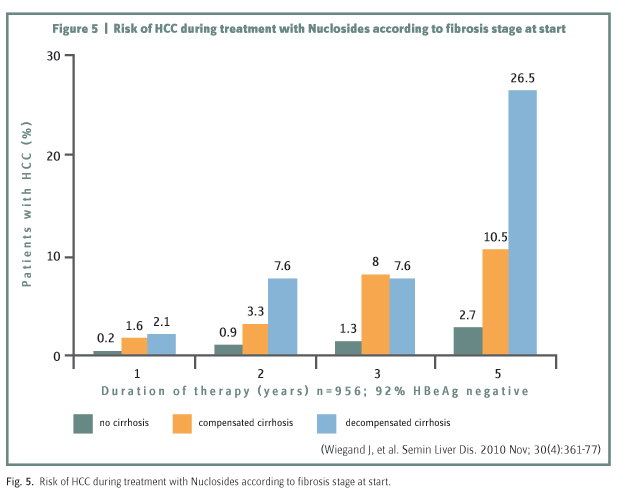

Even if HBV DNA is effectively suppressed, HCC can still develop particularly in the decompensated cirrhotic group as shown recently in a long-term follow-up study from Greece (figure 5)17. Whereas the number of transplants for end-stage liver disease from hepatitis B in the USA decreased by 47% over 7 years reflecting the excellent control of inflammatory disease by antiviral treatment, the number being transplanted for HBV associated HCC increased by 72%18. Surveillance for HCC, therefore, remains an important part of long-term management.

References

Pockros PJ, Hamzeh FM, Martin P, Lentz E, Zhou X, Govindarajan S, et al. Histologic outcomes in hepatitis C-infected patients with varying degrees of virologic response to interferon-based treatments. Hepatology 2010; 52(4):1,193 – 1,200.

Darling JM, Aerssens J, Fanning G, McHutchison JG, Goldstein DB, Thompson AJ, et al. Quantitation of pretreatment serum IP-10 improves the predictive value of an IL28B gene polymorphism for hepatitis C treatment response. Hepatology 2010; 52(4) Suppl:128A.

Pearlman BL, Ehleben C, Saifee S. Treatment extension to 72 weeks of Peginterferon and Ribavirin in hepatitis C genotype 1-infected slow responders. Hepatology 2007; 46(6):1,688 – 1,694.

Pattullo VH. Morbid obesity and HCV: management strategies. In: Clinical Dilemmas in Viral Liver Disease. Graham R. Foster, K. Rajender Reddy, Eds. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, UK. 2010; 61 – 64.

Poynard T, Colombo M, Bruix J, Schiff E, Terg R, Flamm S, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin: effective in patients with hepatitis C who failed interferon alfa/ribavirin therapy. Gastroenterology 2009; 136(5):1,618 – 1,628.e2.

Jensen DM, Marcellin P, Freilich B, Andreone P, Di Bisceglie A, Brandao-Mello CE, et al. Re-treatment of patients with chronic hepatitis C who do not respond to peginterferon-alpha2b: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009; 150(8):528 – 540.

McHutchison JG, Everson GT, Gordon SC, Jacobson IM, Sulkowski M, Kauffman R, et al. Telaprevir with peginterferon and ribavirin for chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 2009; 360(18):1,827 – 1,838. Erratum in: N Engl J Med. 2009; 361(15):1,516.

Kwo PY, Lawitz EJ, McCone J, Schiff ER, Vierling JM, Pound D, et al. Efficacy of boceprevir, an NS3 protease inhibitor, in combination with peginterferon alfa-2b and ribavirin in treatment-naive patients with genotype 1 hepatitis C infection (SPRINT-1): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2010; 376(9742):705 – 716. Erratum in: Lancet. 2010; 376(9748):1,224.

Gane EJ, Roberts SK, Stedman CA, Angus PW, Ritchie B, Elston R, et al. Oral combination therapy with a nucleoside polymerase inhibitor (RG7128) and danoprevir for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 infection (INFORM-1): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2010; 376(9751):1,467 – 1,475.

Weisberg IS, Jacobson IM. Rethinking the inactive carrier state: management of patients with low-replicative HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B and normal liver enzymes. In: Clinical Dilemmas in Viral Liver Disease. Graham R. Foster, K. Rajender Reddy, Eds. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, UK. 2010; 129 – 134.

Alazawi W, Foster GR. Advances in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis B. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008; 21(5):508 – 515.

Fattovich G, Olivari N, Pasino M, D’Onofrio M, Martone E, Donato F. Long-term outcome of chronic hepatitis B in Caucasian patients: mortality after 25 years. Gut. 2008; 57(1):84 – 90.

Nguyen MH, Garcia RT, Trinh HN, Lam KD, Weiss G, Nguyen HA, et al. Histological disease in Asian-Americans with chronic hepatitis B, high hepatitis B virus DNA, and normal alanine aminotransferase levels. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009; 104(9):2,206 – 2,213.

Kumar M, Sarin SK, Hissar S, Pande C, Sakhuja P, Sharma BC, et al. Virologic and histologic features of chronic hepatitis B virus-infected asymptomatic patients with persistently normal ALT. Gastroenterology 2008; 134(5):1,376 – 1,384.

Chee GM, Poordad FF. HBV therapy following unsuccessful interferon therapy: how do you see the role for oral therapies? In: Clinical Dilemmas in Viral Liver Disease. Graham R. Foster, K. Rajender Reddy, Eds. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, UK. 2010; 188 – 191.

Jaroszewicz J, Calle Serrano B, Wursthorn K, Deterding K, Schlue J, Raupach R, et al. Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) levels in the natural history of hepatitis B virus (HBV)-infection: a European perspective. J Hepatol. 2010; 52(4):514 – 522.

Wiegand J, van Bommel F, Berg T. Management of chronic hepatitis B: status and challenges beyond treatment guidelines. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Nov; 30(4):361 – 377.

Kim WR, Terrault NA, Pedersen RA, Therneau TM, Edwards E, Hindman AA, et al. Trends in waiting list registration for liver transplantation for viral hepatitis in the United States. Gastroenterology 2009; 137(5):1,680 – 1,686.

Απρίλιος 2011