- HYGEIA

- Vision & Mission

- Timeline

- Organizational structure

- Press Releases

- Social responsibility

- Awards and Distinctions

- Human Resources

- Scientific & Training activities

- Articles – Publications

- Our Facilities

- Magazines

- Healthcare Programs

- Doctors

- Services

- Medical Divisions & Services

- Imaging Divisions

- Departments

- Units

- Centers of Excellence

- Emergency – Outpatient

- Nursing Service

- Ambulances

- Patients

Οsteoarthritis

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a condition that affects your joints, causing pain and stiffness. It’s by far the most common form of joint disease, affecting people all over the world. It’s sometimes called degenerative joint disease.

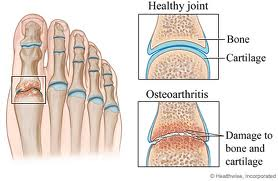

How does a normal joint work?

A joint is where 2 or more bones meet. The joint lets your bones move freely but within limits.

What happens to a joint with osteoarthritis?When your joint has osteoarthritis its surfaces become damaged and it doesn’t move as well as it should do. The following happens:

- The cartilage becomes rough and thin.

- The bone at the edge of the joint grows outwards, forming bony spurs called osteophytes.

- The synovium may swell and produce extra fluid, causing the joint to swell.

- The capsule and ligaments slowly thicken and contract.

In severe osteoarthritis the cartilage can become so thin that your bones start to rub against each other and wear away. The loss of cartilage, the wearing of bone and the osteophytes can alter the shape of your joint, forcing the bones out of their normal position.

What are the symptoms of osteoarthritis?

Symptoms can include:

- pain

- stiffness

- a grating or grinding sensation (crepitus) when you move the joint

- soft or hard swellings

The main symptoms of osteoarthritis are:

- pain (particularly when you’re moving the joint or at the end of the day)

- stiffness (especially after rest – this usually eases after a minute or so as you get moving)

- crepitus, a creaking, crunching, grinding sensation when you move the joint

- hard swellings (caused by osteophytes)

- soft swellings (caused by extra fluid in the joint)

Other symptoms can include:

- the joint giving way because your muscles have become weak or the joint structure is less stable

- the joint not moving as freely or as far as normal

- the muscles around your joint looking thin or wasted

Symptoms can change for no obvious reason. Some people find that changes in the weather (especially damp weather and low pressure) make the pain worse. Others find the pain varies depending on how active they’ve been.

What causes osteoarthritis?

Almost anyone can get osteoarthritis but you’re at a greater risk if:

- you’re in your late 40s or older

- you’re overweight

- you are a woman

- your parents had it

- you’ve had a previous joint injury

- your joints have been damaged by another disease (e.g. gout or rheumatoid arthritis).

Many factors can increase the risk of osteoarthritis. It’s most common if:

- you’re in your late 40s or older. This might be because your muscles have become weaker, your body is less able to heal itself or your joints have gradually worn out over time.

- you’re a woman. Osteoarthritis is more common and more severe in women, especially osteoarthritis of the hands and knees.

- you’re overweight. This increases the chances of developing osteoarthritis, particularly of the knee, and of it becoming progressively worse.

- your parents have had osteoarthritis. Nodal osteoarthritis, which affects the hands of middle-aged women, runs strongly in families. Some rare forms of osteoarthritis that start at an early age are linked with genes that affect collagen, a vital part of cartilage. Genetic factors play a smaller but significant part in osteoarthritis of the hip and knee.

- you’ve had a previous joint injury

- a major injury or operation on a joint may lead to osteoarthritis in that joint

- hard, repetitive activity or a physically demanding job can increase the risk

- you were born with or have developed a joint abnormality. This can lead to more severe osteoarthritis, which can develop at an earlier age than normal

- you have another type of joint disease. Osteoarthritis can develop as a result of damage from a different kind of joint disease, such as rheumatoid arthritis or gout.

Which joints are affected?

Osteoarthritis can affect any joint, but it most commonly affects the following:

- knees

- hips

- neck and back

- base of the big toe

- hands

- shoulders

Osteoarthritis of the knee

What happens?

The knees are one of the joints that are most commonly affected by osteoarthritis. This is probably because they have to withstand extreme stresses, twists and turns. Osteoarthritis can affect the main surfaces of your knee joint and the cartilage under your kneecap (patella).It usually affects both knees, and you’re most likely to feel pain at the front and sides of your knees.

Your knees may become bent and bowed if you have severe osteoarthritis. Your knee joint may become unstable and give way when you put weight on it. This is usually because of muscle weakness or damage to the ligaments.Who gets it?

You’re most likely to develop osteoarthritis in your knee if:- you’re a woman – women are twice as likely as men to develop osteoarthritis of the knee

- you’re in your late 50s or older

- you’re overweight

- you have nodal osteoarthritis (particularly if you’re a woman)

- you had a previous sporting injury (such as a torn meniscus or ligaments)

- you’ve had an operation to remove torn cartilage (a meniscectomy)

Osteoarthritis of the hip

What happens?

Osteoarthritis of the hip is very common and can affect one or both hips. You’re most likely to feel pain deep at the front of your groin, but you may also feel it at the side and front of your thigh, in your buttock or down to your knee. This is called radiated pain. You may find the affected leg seems a little shorter than the other because of the bone on either side of your hip being crunched up if you have severe osteoarthritis.Who gets it?

You’re most likely to develop osteoarthritis of the hip if:- you’re in your late 40s or older

- you had hip problems at birth or in childhood (for example congenital dislocation or Perthes’ disease)

- you’ve had a physically demanding job (for example farming)

Sometimes there’s no obvious cause. Men and women are equally as likely to develop osteoarthritis of the hip. People of Chinese and Afro-Caribbean origin rarely get it, though we don’t know why.

Osteoarthritis of the hands

What happens?

Osteoarthritis of the hands usually happens as part of nodal osteoarthritis. It most often affects the base of your thumb and the joints at the ends of your fingers. Other finger joints can also be affected. The joints become red, swollen and tender, especially when the condition first appears. Firm knobbly swellings form on the back of the end joints of your fingers over several years. These are called Heberden’s nodes. The pain and tenderness often improve once these are fully formed. Your fingers usually function well even though they’re knobbly and sometimes slightly bent. The joint at the base of your thumb may continue to be a problem.Who gets it?

You’re more likely to develop it if:- you’re a woman

- you’re in your 40s or 50s (around the time of the menopause)

- your parents (especially your mother) had it – nodal osteoarthritis has a stronger genetic influence than other forms of osteoarthritis

You’re more likely to develop osteoarthritis of the knee and occasionally a few other joints if you have nodal osteoarthritis in middle age.

Osteoarthritis of the neck and back

What happens?

Osteoarthritis of the neck and back is very common. It’s often called spondylosis. It’s not the most frequent cause of back or neck pain and often doesn’t cause any problems.Osteoarthritis of the foot

What happens?

Osteoarthritis of the foot usually affects the base of your big toe. Your toe may:- become stiff (hallux rigidus), which can make it difficult and painful to walk

- become bent (hallux valgus), which can lead to painful bunions

Osteoarthritis of the shoulder

What happens?

Osteoarthritis of the shoulder is quite rare but it can sometimes follow a previous injury or abnormal stresses. It can occur in the shoulder itself (the glenohumeral joint) or between your collarbone and shoulder (the acromioclavicular joint). It can cause pain and reduce mobility.How is osteoarthritis diagnosed?

Your doctor will make a diagnosis based on your symptoms and an examination. X-rays are the most useful tests to confirm a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although they won’t often be needed.Your doctor will make a diagnosis based on your symptoms and an examination. During the examination, they will check for:

- tenderness over the joint

- creaking and grating of the joint (crepitus)

- bony swelling

- excess fluid

- restricted movement

- instability in the joint

- thinning of the muscles that support the joint

What tests are there?

X-rays are the most useful tests to confirm a diagnosis of osteoarthritis, although they won’t often be needed. X-rays may show changes such as osteophytes or narrowing of the space between bones. They’ll also show any calcium deposits within your joint.X-rays aren’t a good indicator of how much pain or disability you’re likely to have – some people have a lot of pain from minor joint damage but others have little pain from severe damage.

There’s no blood test for osteoarthritis but they can be used to rule out other conditions.

What treatments are there for osteoarthritis?

Your treatment will vary depending on how severe your pain is. You may find that a combination of over-the-counter painkillers and self-help methods are all you need, but if your pain is severe your doctor may suggest the following treatment:- capsaicin cream

- stronger painkillers (e.g. tramadol) for more intense pain

- cortisone injections into the painful joint

- transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS)

- surgery, including joint replacement

There’s no cure for osteoarthritis as yet, but there are a number of treatments that can help ease symptoms and reduce the chances of your arthritis becoming worse.

Tablets and creams

Painkillers (analgesics) help with pain and stiffness but they don’t affect the arthritis itself and won’t repair the damage to your joint.- They’re best used occasionally when you’re in pain or when you’re likely to be exercising.

- Paracetamol (Depon or Panadol) is usually the best and most well-tolerated painkiller, but make sure you take the right dose because many people take too little – try 1 gram (usually 2 tablets) 3 or 4 times a day.

- Combined painkillers (e.g. co-codamol, co-dydramol) contain paracetamol and a second codeine-like drug, so they may be helpful for more severe pain. Because they’re stronger than painkillers, they’re more likely to cause side-effects, such as dizziness and constipation.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), for example ibuprofen or naproxen, may be recommended if inflammation in a joint is contributing to your pain and stiffness.

- NSAIDs can sometimes have side-effects, but your doctor will take precautions to reduce the risk of these. They may suggest the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible time and prescribe another drug called a proton pump inhibitor to help protect your stomach from digestive problems.

- NSAIDs also carry a slightly increased risk of a heart attack or stroke, so your doctor will be cautious about prescribing them if there are other factors that increase your overall risk (e.g. you smoke, have circulation problems or diabetes or have high blood pressure or cholesterol).

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory creams and gels are a good option if you have trouble taking NSAID tablets. They’re particularly helpful for osteoarthritis of the knee or hand but not for deep joints like the hip.

- NSAID creams and gels can be applied directly onto painful joints 3 times a day and there’s no need to rub them in – they absorb through your skin on their own.

- They’re extremely well tolerated because very little is absorbed into your bloodstream.

- You can tell within a few days whether they’ll help with your pain.

- Capsaicin cream is made from the pepper plant (capsicum) and is an effective and well-tolerated painkiller. It’s particularly useful for osteoarthritis of the hand and knee.

- Capsaicin cream is only available on prescription and needs to be applied 3 times a day.

- Most people feel a warming or burning sensation when they first use it, but this generally wears off after several days.

- The pain relief starts after a few days and you should try it for at least 2 weeks before deciding if it’s helped.

- Stronger painkillers, for example opioids/anti-inflammatories, may be prescribed if you have severe pain and other medications don’t work well enough.

- Stronger painkillers are more likely to have side-effects, especially nausea, dizziness and confusion, so you’ll need to see your doctor regularly and report any problems.

- Some opioids can be given as a plaster patch to wear on your skin, which can give pain relief for a number of days.

- Stronger painkillers are only available on prescription.

- Because these treatments work in different ways, you can combine them for greater pain relief. Ask your chemist or doctor for advice on safe combinations.

Other treatments

Applying warmth or cold to your affected joint can relieve pain and stiffness.- Heat lamps are popular, but a hot-water bottle or reheatable pad (available from most chemists) are just as effective.

- An ice pack can also ease pain.

- Don’t apply a hot or cold pad directly onto the skin.

Cortisone injections are sometimes given directly into a particularly painful joint. The injections can start working within a day or so and may improve pain for several weeks or months, especially in a knee or thumb.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) can be used for pain relief, although research evidence suggests that it doesn’t work for everyone. A TENS machine is a small electronic device that sends pulses to the nerve endings via pads placed on the skin. The device produces a tingling sensation which is thought to modify the pain messages sent to the brain. TENS machines are applied by physiotherapists.

Surgery (including joint replacement) may be recommended if you have severe pain that do not subside with other treatments or mobility problems.- Joint replacements can give substantial pain relief in cases where other treatments haven’t given enough help.

- If your knee locks an operation to wash out loose fragments of bone and other tissue from the joint can be done – this is called arthroscopic lavage.

- © 2007-2024 HYGEIA S.M.S.A.

- Personal Data Protection Policy

- COOKIES Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Credits

- Sitemap

- Made by minoanDesign

Ο ιστότοπoς μας χρησιμοποιεί cookies για να καταστήσει την περιήγηση όσο το δυνατόν πιο λειτουργική και για να συγκεντρώνει στατιστικά στοιχεία σχετικά με τη χρήση της. Αν θέλετε να λάβετε περισσότερες πληροφορίες πατήστε Περισσότερα ή για να αρνηθείτε να παράσχετε τη συγκατάθεσή σας για τα cookies, πατήστε Άρνηση. Συνεχίζοντας την περιήγηση σε αυτόν τον ιστότοπο, αποδέχεστε τα cookies μας.

Αποδοχή όλων Άρνηση όλων ΡυθμίσειςCookies ManagerΡυθμίσεις Cookies

Ο ιστότοπoς μας χρησιμοποιεί cookies για να καταστήσει την περιήγηση όσο το δυνατόν πιο λειτουργική και για να συγκεντρώνει στατιστικά στοιχεία σχετικά με τη χρήση της. Αν θέλετε να λάβετε περισσότερες πληροφορίες πατήστε Περισσότερα ή για να αρνηθείτε να παράσχετε τη συγκατάθεσή σας για τα cookies, πατήστε Άρνηση. Συνεχίζοντας την περιήγηση σε αυτόν τον ιστότοπο, αποδέχεστε τα cookies μας.